Studio Ghibli’s Hidden Legacy: Uncovering Their Unsung Works

Between short films, music videos, commercials, and more, there’s a lot more to one of the world’s most famous animation studios than meets the eye. In this essay and the accompanying video, I explore the evolution of Studio Ghibli by examining their work that stands outside their generally recognized canon.

When you think of Studio Ghibli, there is probably a very specific image that comes to mind, most likely of Hayao Miyazaki’s distinctive and gorgeous hand-drawn animation style, whether you think of Totoro, Princess Mononoke, Howl’s Moving Castle, or one of his many other films. But Studio Ghibli is much more than that, and you might be surprised at how many times they’ve stepped outside their comfort zone and dipped their toes into completely unfamiliar territory to them. Between short films, commercials, music videos, video games, a television show, a French co-production by an acclaimed Dutch animator, and even a live-action arthouse film, the studio has never been afraid of looking past the expectations their most fervent fans have for them.

Chapter 1: Yoshiyuki Momose (Music videos, commercials, and CGI, oh my!)

Studio Ghibli is often referred to as a rare remaining pillar of mainstream traditional animation, which leads many to react with disgust at the prospect of the studio exploring avenues beyond that, particularly CGI. At least, that’s how most people reacted to the studio’s first fully CGI film, Earwig and the Witch.

But, in fact, Ghibli had been experimenting with CGI for decades before that film came out, and was very much on the cutting edge of incorporating CGI and digital techniques into their traditionally animated work. While many figures were involved with the development of CGI at Studio Ghibli, I find it interesting to focus on Yoshiyuki Momose, who first joined Studio Ghibli as a storyboard artist, layout artist, and key animator on Grave of the Fireflies.

However, his work on Princess Mononoke, which released in 1997, really set the stage for what his role would be at the studio going forward, and began to establish him as a distinct voice from Ghibli’s mainstay directors, without ever even getting a chance to direct a feature. See, around this time, Hayao Miyazaki was beginning to think about how CG animation could supplement the traditional hand-drawn work that had thus far defined his films. This was first seen in the music video On Your Mark, which Miyazaki directed while taking a break from Princess Mononoke due to writer’s block.

When Miyazaki decided to carry some of the CG techniques from that music video into Princess Mononoke, he brought Yoshiyuki Momose on as a CG producer. As Momose continued working with the studio, his work would continue to break from Ghibli’s traditional style, as he was tasked with directing commercials, music videos, and short films. Momose’s first work as a director was Ghiblies Episode 2, which was a short film released alongside The Cat Returns in 2002. Ghiblies Episode 2 contains an interesting blend of different animation styles, shifting between them from scene to scene to designate different distinct tones. One segment has beautiful backgrounds that look right out of a storybook, as if they were drawn with colored pencils. Another uses a more modern style that incorporates stark shadows and a muted color palette that make it look like a noir, or maybe something out of Ghost in the Shell.

Another looks like it’s drawn with a thick marker, using simple character designs and backgrounds, an uncommon sight for a Studio Ghibli film. And then there’s the very first scene of the short, which uses CGI in a fascinating way, seeming to emulate a hand-drawn style while still clearly being computer generated. It’s actually pretty impressive what they managed to do with the medium back in 2002. The CGI is noticeably somewhat rudimentary, but that only makes it all the more interesting. It’s clear that Ghiblies was used somewhat as a playground for experimentation, and this opening segment serves as the most prominent evidence for that being the case.

After Ghiblies Episode 2, Momose went on to direct a couple of commercials for House Food, which Miyazaki had also previously done. In Momose’s commercials, the characters themselves are animated in a very typically Ghibli hand-drawn style, while the backgrounds utilize CGI and digital compositing methods to create the illusion of camera movement. It may not seem like much, but these commercials do point towards Momose’s continued interest in finding new ways to blend CGI and hand-drawn animation, and the same goes for Hayao Miyazaki and the studio as a whole.

In 2000, Momose was tasked with running a new spinoff studio of Studio Ghibli called Studio Kajino. His first directorial projects at this new subsidiary were a series of music videos for the electronica band Capsule. Through these music videos, Momose was really able to experiment in novel ways. The style exhibited in them is not remotely identifiable as the work of Studio Ghibli, and it’s clear that Momose was aiming for something else entirely. He was able to create something rather distinct through the unnatural, blocky colors and the almost invisible lineart on the characters.

And, of course, the use of CGI was incredibly impressive, adding to the pleasing futuristic aesthetic. The CG style here feels reminiscent of that Ghiblies Episode 2 segment, but has clearly been taken a step further, as the blending of styles feels pretty much seamless here. From what I can tell, many of the backgrounds are CG, as well as some objects such as cars, whereas traditional animation is used for most of the character animation, but the distinctive color palette and overall style allow both media to work together in harmony.

Momose’s ability to find harmony between traditional and computer-generated animation would later have an unexpected but fitting application when Studio Ghibli was approached by the game developer Level 5 about collaborating on a video game project. The project, Ni no Kuni, would incorporate a blend of traditionally animated cutscenes, in-engine cutscenes, and gameplay, and it was important for the aesthetic to remain intact even as the game jumped from different media. Yoshiyuki Momose ended up being the animation director on this project, which involved overseeing not only the traditional animation work on Ghibli’s side, but also Level 5’s in-engine cutscenes, which included drawing storyboards, staging the scenes, and even directing motion capture sessions.

This ambitious infusion of Studio Ghibli’s animation into a JRPG ended up being a success, with both Ghibli and Level 5 doing their part to bring the game to such heights. Ni no Kuni received high acclaim from critics and players, with many praising the Ghibli charm that is present throughout, not only in the segments animated by Ghibli themselves, but also in the in-engine cutscenes and the gameplay, where Level 5 sought to recreate some of that Ghibli magic.

In 2014, when Studio Ghibli went on hiatus in the wake of Hayao Miyazaki’s retirement, Yoshiyuki Momose was one of many staff members who joined the newly formed Studio Ponoc, which served as a sort of spiritual successor to Studio Ghibli, even if Ghibli itself would eventually return from the dead. At Ponoc, Momose worked on the film Mary and the Witch’s Flower as a key animator before directing a segment of the studio’s anthology film Modest Heroes.

After that, he went on to direct a feature film for the first time, which was, perhaps fittingly, a movie adaptation of the NiNoKuni video game series. Neither Ghibli nor Ponoc had any involvement with this adaptation. Momose is also at the helm of Studio Ponoc’s second feature length film, The Imaginary, which is set to release in Japan later this year, and from the footage that has been made public so far, the film seems to make more visible use of CGI than Ghibli’s feature films, contributing to an aesthetic that allows the film to step outside the shadow Studio Ghibli casts over Studio Ponoc.

Chapter 2: Miyazaki & Son (or, the purist’s nightmare)

Studio Ghibli’s exploration of CGI was not limited to Yoshiyuki Momose’s work, though, as later both Miyazakis would take a crack at their own work that heavily incorporates CGI. One such project was Ronja, the Robber’s Daughter, a television series directed by Goro Miyazaki that used cell-shading to replicate a traditional anime style with CGI.

Many of the backgrounds in the series were hand-drawn, but the characters were computer-generated, with the goal being to seamlessly combine these two elements without taking away from the magic of traditional animation. Reactions to this style were mixed. Cell-shading has been used in many anime series, and although strides in the technology have been made over time, it will always have its supporters and detractors. This was the first time Ghibli fans rang the alarm bells over the sanctity of their beloved 2D animation studio being trampled on, as although the CG animation on the series was handled by a different studio called Polygon Pictures, Ghibli’s brand was predictably used heavily in the show’s marketing, hailed as Ghibli’s first television series.

The elder Miyazaki would also get his chance at a CGI work, as his first post-retirement project was a short film for the Ghibli Museum called Boro the Caterpillar, which was the first time he would animate a main character using CGI. Producer Toshio Suzuki was the one to suggest using CGI, as he believed the new challenge would spark creativity in the recently-retired Miyazaki. For his part, Miyazaki mentioned being excited at the possibility of using CGI to achieve things he had wanted to do but wouldn’t be able to accomplish by hand. Although I have not seen the full short, which is exclusive to the Ghibli Museum’s theater, the scarce footage available indicates that Miyazaki’s attention to detail and visual aesthetic were not hindered by the use of this new medium, and that under his careful direction it could be used well.

Not long after this, Ghibli released its first full CGI feature film, Earwig and the Witch, which was directed by Goro Miyazaki. Rather than the cell-shading style paired with hand-drawn backgrounds of Goro’s previous CGI work, Earwig was completely rendered in a more conventional CGI style, somewhat reminiscent of another CGI anime, the latest Lupin the Third entry. This stylistic decision garnered significant criticism from fans and critics. To me, the animation is not the film’s worst problem, but it’s also a film that cannot hide behind the beauty of its animation. With any other Studio Ghibli film, you can rest assured knowing that the very least you can get out of the film is some gorgeous animation, but with Earwig, any issues with the film’s plot and characters are laid bare due to the relatively generic CGI.

It feels like a shame, considering how much interesting work had been done by the studio with CGI up to this point. From Yoshiyuki Momose’s experimental music video animation to Hayao Miyazaki’s artistically faithful CG caterpillar, it seems as if the studio had every opportunity to use CGI in interesting, novel ways, but when it came to actually creating a feature, responsibility was delegated not to Hayao Miyazaki, who was hard at work on his next hand-drawn feature, nor to Yoshiyuki Momose, who was working with Studio Ponoc on his own next feature, and all that experimentation amounted to very little in the end.

Chapter 3: Hideaki Anno (Ghibli’s adventures in live-action)

On the subject of Studio Kajino, one fascinating project in this Ghibli subsidiary’s brief filmography is Hideaki Anno’s 2000 live-action film Ritual. It feels strange to say that Studio Ghibli has produced a live-action film, and even stranger to think that such a film would be coming from the director most famous for the animated Neon Genesis Evangelion franchise.

But Hideaki Anno, Studio Ghibli, and Miyazaki are all intrinsically intertwined with one another, owing to a long-standing relationship that began with the very film that created Studio Ghibli, Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, which also happened to launch Anno’s professional career. Anno would return to Ghibli once more to work on Grave of the Fireflies before serving as one of the founding members of Gainax, where his first work was the TV series Nadia: The Secret of Blue Water. Funny enough, that series actually began as an unproduced Hayao Miyazaki project at Toho before being resurrected decades later with some semblance of Miyazaki’s plot outline intact and Hideaki Anno now at the helm.

When Anno was directing his most famous series, Evangelion, Studio Ghibli came on as an animation studio and co-producer for the eleventh episode, almost as if returning the favor of Anno contributing to their films all those years prior. Later, they would also contribute to the third and fourth films of Anno’s Rebuild of Evangelion series. This ongoing, deep-rooted relationship was undoubtedly what motivated Ghibli to agree to producing Anno’s live-action film.

This move also speaks to how willing Ghibli was to diversify and experiment in order to expand their brand and influence. They weren’t just appealing to families and animation fans, they were also targeting cinephiles and those interested at a deeper understanding of the artists behind the animation. They wanted their label to carry a certain prestige, even when applied to works outside their immediate canon. Ritual remains an oddity in the Ghibli filmography, though, as to this day the only other live-action feature they’ve involved themselves with is the 2001 film Transparent: Tribute to a Sad Genius, which was also produced under the Kajino label.

As far as short films go, Studio Ghibli also collaborated with Hideaki Anno on a live-action prequel to Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind, titled Giant God Warrior Appears in Tokyo. The film was written and produced by Anno and directed by his frequent collaborator Shinji Higuchi, who co-directed Shin Godzilla and solo directed Shin Ultraman. The film’s visual aesthetic is very similar to those films, and considering it predates Shin Godzilla by a few years, it feels almost like a prototype for what Anno and Higuchi would later do with a feature-length kaiju film.

Unlike Ritual, this short film is attributed to Studio Ghibli rather than Studio Kajino, even opening with Ghibli’s classic logo, albeit in red instead of their usual blue. For this reason, or perhaps just due to the relative obscurity of Ritual and Transparent, many publications have referred to this short as Ghibli’s first live-action film, which I suppose can be true or false depending on how you look at it. Giant God Warrior is quite a visually striking film, utilizing a blend of live-action, CGI, and puppetry, but besides the Nausicaa connection it’s far more identifiable as the work of Anno than as a Ghibli film. I guess that’s the lesson of the day, though: You can’t exactly put Studio Ghibli in an aesthetic box, and they seem more than happy to yield to the creative ambitions of an artist like Anno.

Chapter 4: Conclusion (Authorial control and experimentation)

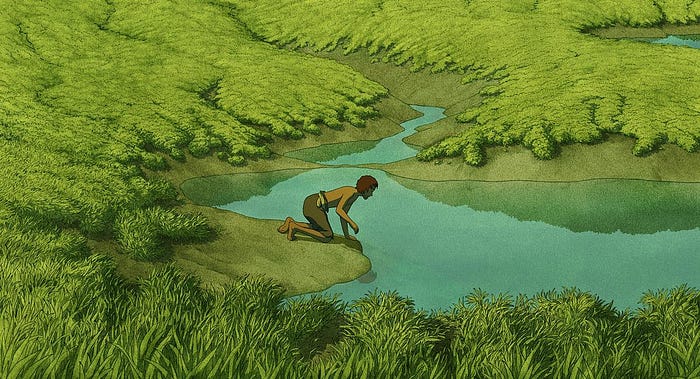

Case in point, as strange as Ghibli’s involvement with Ritual was, this kind of deviation from their usual strategy would be echoed sixteen years later when the studio agreed to co-produce the film The Red Turtle, which was the feature directorial debut of acclaimed Dutch animator Michaël Dudok de Wit.

It was highly unusual for Ghibli to produce a film that wasn’t developed in-house, but this collaboration ignored that convention simply because of the great respect the main Ghibli trio of Miyazaki, Takahata, and Suzuki had for this animator’s work. In co-producing the film, they were able to lend support without taking over authorial control, and they were able to bring it to audiences familiar with the Ghibli brand who might not have otherwise discovered the film.

A similar instance of Ghibli lending support and authorial control to an artist they respect was the OVA Iblard Jikan, which was directed by Naohisa Inoue. Inoue is a surrealist fantasy artist whose striking paintings inspired the opulent fantasy sequences in Whisper of the Heart.

In 2006, Hayao Miyazaki directed the Ghibli Museum exclusive short film The Day I Bought A Star, which was based on a story by Inoue and served as an adaptation of his paintings. That same year, Inoue was also given the opportunity to direct his own work at Ghibli, which came in the form of this OVA, in which his paintings were brought to life through subtle movements and the inclusion of foreground characters. While it’s almost a stretch to say that a film like this even had a director, considering it’s essentially a slideshow of paintings with minor digital enhancements performed on them, it does seem like a clear gesture from Studio Ghibli for them to give Inoue this opportunity. While Inoue’s work was incorporated into someone else’s story in Whisper of the Heart, here his art could breathe and live a life of its own, handing the keys back to the artist. As with The Red Turtle and Ritual, Ghibli’s involvement clearly came from a place of respect for the artist rather than a need to control their output.

Short films, music videos, commercials, and more have served as great sandboxes for Studio Ghibli to experiment with, not only in terms of developing and applying new techniques, but also in terms of giving new voices a chance at the helm without dedicating the resources that would be required for a feature. Their last three short films have each been unprecedented in their own ways: Giant God Warrior Appears in Tokyo was their first live-action short film, Boro the Caterpillar had Miyazaki’s first CG-animated main character, and Zen — Grogu and Dust Bunnies, which released last year, was uncharacteristically tied to another company’s IP.

From the outside, Ghibli may even seem like a “safe” studio, one that has played by the same rules for the decades of its existence, but they have never been averse to experimentation, nor to pushing new boundaries, and they continue not to be even as the studio’s future is thrown into question. As much as they’re a brand that owes a lot to nostalgia, the fact that they’ve maintained relevance for this long doesn’t come down to them clinging to the past, but instead to their ability to evolve over time, the way Miyazaki began experimenting with CGI and digital techniques at the turn of the century, the way Takahata has never been afraid to try a new style and stand apart from his fellow Ghibli colleague.

They would not be where they are if they didn’t position themselves squarely in the present. While maybe that doesn’t quite lift the sting of the studio putting out something as vacant as Earwig and the Witch, if the studio is to continue existing in any capacity, I hope that they will continue to allow themselves to evolve, rather than trying to recreate the lightning in a bottle held by their most popular films.

Invaluable information was provided by Rayna Denison’s book Studio Ghibli: An Industrial History. Additional material comes from the Japanese Movie Database (jmdb.ne.jp) and the Ghibli wiki (nausicaa.net). All images belong to Studio Ghibli and associated brands.